André Breton’s Le Manifeste du Surréalism (Manifesto of Surrealism) in 1924 sparked a cultural movement that unlocked limits. Surrealist artistic philosophy follows the premise that Breton set forth—that “omnipotence of dreams” and “disinterested play of thought” take precedence over logic and reason. The forefathers of the movement felt inspired by ideas surrounding the power of unconscious thought, and used writing and art to reconcile the unconscious mind with rational life.

A Guide to Surrealist Poetry

1. Beginnings in Dadaism and Freudian inspiration: The Surrealist movement grew out of Dadaism, which broke codes regarding society’s accepted values and conventions. Surrealism aimed to be an instrument of knowledge, as those who followed the movement believed that the subconscious contained true reality. Poets who followed the surrealist movement agreed with Freud’s theory that the unconscious mind is deeper than the conscious mind.

2. A higher reality and point sublime: Surrealism involves the concept of a reality that is higher than the reality that individuals experience in everyday life. Poets who followed the movement focused on the reality created by the waking consciousness, which unites imagination and the real world, subjectivity and objectivity, and dream states and wakefulness. Breton stated in The Communication Vessels that the real and dream worlds are the same; the mind in each state of being communicates like two connected vessels. This principle is also known as point sublime, which is the realization of surreal unity—the point at which contrasts merge, such as life and death, beauty and ugliness, the past and future.

3. The marvelous and objective chances: The concept of the marvelous, or aggravated beauty, had a large role in Surrealist poems. Marvelous concepts depicted in these poems portray the ongoing anxiety that underlies the human experience. The involuntary shudder that marvelous images cause is the result of objective chances—the juxtaposition of two terms that seemed to conflict with each other, but are secretly related.

4. Delirious love: Following Breton’s lead in the Second Manifesto, Surrealists celebrate love as the only idea that unites every individual to the idea of life, even if for a brief moment. Therefore, passionate commitment is a liberating force.

5. Automatic writing: Some surrealist writers used automatism. This means that as a poet writes, there is no conscious control over thoughts. She or he writes whatever comes to mind. According to Breton, a Surrealist poet should not filter, select or shape his or her writing. The words should be raw and vivid.

Examples of Classic Surrealist Poetry

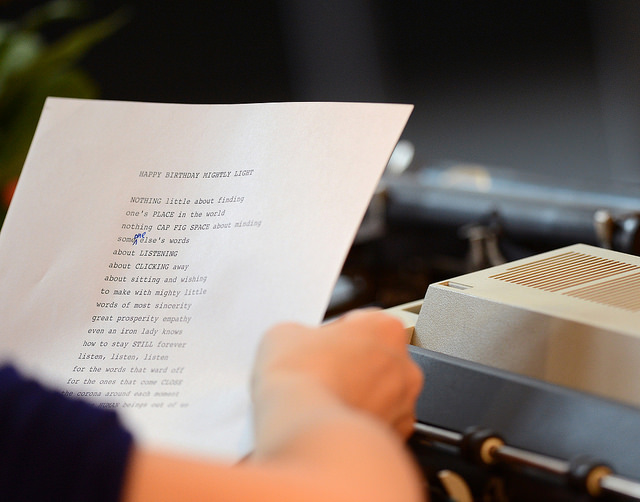

Choose Life (excerpt)

Choose life instead of those prisms with no depth even if their colors are purer

Instead of this hour always hidden instead of these terrible vehicles of cold flame

Instead of these overripe stones

Choose this heart with its safety catch…

-André Breton

Arp

Turns without reflections to the curves without smiles of shadows with mustaches, registers the murmurs of speed, the miniscule terror, searches under some cold cinders for the smallest birds, those which never close their wings, resist the wind.

-Paul Éluard

Series

For the splendour of the day of happinesses in the air

To live the taste of colours easily

To enjoy loves so as to laugh

To open eyes at the final moment

She has every willingness.

– Paul Éluard

Enigmas (excerpt)

You’ve asked me what the lobster is weaving there with

his golden feet?

I reply, the ocean knows this.

You say, what is the ascidia waiting for in its transparent

bell? What is it waiting for?

I tell you it is waiting for time, like you…

-Pablo Neruda

Mobius Strip

The track I’m running on

Won’t be the same when I turn back

It’s useless to follow it straight

I’ll return to another place

I circle around but the sky changes

Yesterday I was a child

I’m a man now

The world’s a strange thing

And the rose among the roses

Doesn’t resemble another rose.

-Robert Desnos

[Photo from Ian Palmer via CC License 2.0]